|

Full disclosure: I 100% stole the idea for this post from Michael John Neill, the man behind the always excellent Genealogy Tip of the Day. He recently wrote a blog post titled "My Boring Ancestors", in which he summarized a few quick and anything-but-boring stories he's learned about his ancestors, and it struck a chord. I admit, I was a bit disappointed when I first started researching my family history back in 2005. While I had no idea what my background really was, I had heard many a grand tale that had been passed down through the generations...all of which almost immediately proved false. Instead, it turned out that the majority of my ancestors were relatively poor farmers, tailors, and labourers from England, Scotland, Wales, and Germany. A handful were moderately successful merchants, fishermen, and businessmen. None of them seemed particularly interesting. And, unless you happen to have a direct relative of great fame or infamy, none of yours will either, at first. The truth is, most people who have ever existed lived fairly ordinary lives in terms of education, career, and hobbies. Most people were educated to the normal point for their era, had a job common for their time, and engaged in pretty standard activities. If you look only at the basic facts found on most genealogy sites, you are unlikely to find anything of much interest. It's only when you really start digging in to your history that you learn no family is boring. If I may offer a few choice examples:  William West, 1828-1908, 3rd great-grandfather William was a farmer from Kentucky. That's about all the census will tell you about him. William was also a man with the urge to travel, abandoning his young wife and child in order to do so. Determined to become a Methodist minister and "fight Mormonism", William ended up making and losing a fortune in the gold rush, and becoming a Mormon. He would go on to marry, have several children, take up a plural wife young enough to be his granddaughter, have a child with her, abandon her and keep the child, become a rancher and missionary, take his entire family to Canada, and help build log cabins in Mountain View.  Bathsheba Layton, 1812-1863, 5th great-grandmother Bathsheba came from a poor farming family and helped out by lace-making. Her brother Christopher's life far overshadows hers, if the history books are to be believed: he was a well-known Mormon Patriarch, founder of several towns, and infamous polygamist; she was a modest homemaker who never left her hometown in England. Yet, she bore a son out of wedlock and gave him her surname, greatly altering the course of our history. She raised him alone for a time, married a man several years her junior, had several more children, and though her parents, siblings, and nieces and nephews all converted to Mormonism and moved to the U.S. and Canada, she absolutely refused, dying a devout Christian in Bedfordshire, England.  Milton Hough, 1863-1927, 3rd great-grandfather Milton was born, and died, in Iowa, and was a carpenter for most of his life. He was also known as a great musician and penman, and apparently wrote and performed scores for local theatre productions. His nephew, Earl, and his grandson, Clarence, were both raised as the adopted sons of his brother, Oliver, and Oliver's wife, Mattie. There's obviously a fascinating story there that I've yet to entirely uncover.  Mary Taylor, 18??-1931, 3rd great-grandmother I've written about Mary before, but I just can't resist writing about her again. On paper, she was just a girl born in England, who, like many others of her time, found herself in the U.S., then Canada, part of a Mormon migration. She got married, she had several kids, she lived on a farm for many of her 6-ish decades on Earth. She also either didn't know how old she was, or lied about it for whatever reason (she personally reported her year of birth as anywhere between 1866 and 1871, and neither of those are likely accurate), and didn't know her nationality (or, again, lied about it for reasons unknown - she claimed she was Scottish, even though her mother was English and her father was Irish). She came to the U.S. at a young age, apparently alone, and lived with her uncle who would subsequently introduce her to the aforementioned William West. She would have a child with him, be abandoned by him, leave the Mormon church, develop tuberculosis, become addicted to morphine, help run a boarding house, meet her husband Henry, regain her health, and start a new family...all before her 30th birthday, even using her earliest given year of birth. These are just a few of my "boring" ancestors. Ancestors who, on paper, were just small-town farmers, carpenters, lace-makers, and boarding house staff. Ancestors who lived in rural Europe and North America. Ancestors that literally no one has ever heard of. And yet, they all have a fascinating story to tell. They were musicians, writers, single-mothers when such a thing was unheard of, and hushed secrets. They were quiet (and loud) resisters, soldiers on both the wrong and right side of history, criminals, and missionaries. They were tradition-bucking outliers and easily persuaded sheep. They had secret children, secret lovers, secret spouses.

They were many things, but not one of them was boring. If there is one piece of advice I could give to anyone just starting out it would be...well, it would be to source everything. But if I could throw in a second piece of advice, it would be to always dig deeper. Birth, death, and marriage certificates aren't going to give you much more than some basic facts. Census records may provide a little insight, but likely won't provide much of interest. If you really want to get to know your family, you need to do the work. Search for their diaries (you'd be amazed how many of them kept one, and how many of their ancestors later published them), look them up in newspaper archives, insist on finding their obituaries. Google their name, look up possible images of them (seriously - you may think your ancestors have no online presence, but I'll bet you a dollar they do). Awkward as it may be, interview your living relatives - these are living, breathing people who can offer first-hand stories about your ancestors. Go to the library; ask about books that may feature your familial surname(s). Once upon a time, I thought my family was boring. Now, I am perpetually blown away by the fascinating lives these seemingly simple people lived. A little digging, a little commitment, and a little luck have taught me that if one thing is for certain, there are no boring families.

0 Comments

The entire world can change in 100 years, and Barbara's life is testament to that. Born to a Scottish father and an English mother, Barbara entered the world on 17 October, 1876. Queen Victoria was halfway through her reign, Benjamin Disraeli was Prime Minister, and the telephone had just been patented. Her father, David, was a tailor who had, for unknown reasons, immigrated to England before meeting her mother, Margaret, and the two married in 1861, eventually going on to have 8 children. Not a lot is known about Barbara's early life, but we can assume, based on what we know of David and Margaret's family history, that she was educated, and learned at least a little about her father's trade. In 1910, when she was 34 and yet to marry, Barbara moved to Canada, alone, for reasons I've still not uncovered. Both of her parents died in 1909, which may have triggered a desire for a major change, but I've thus far not found any reason that Canada specifically would have interested her. In any case, she arrived in Vancouver in 1910, and was in Lethbridge (which would become my own hometown) by 1911. Rumour has it that she met her future husband, Charles Harding, on the ship from England to Canada, and upon becoming engaged, she abandoned British Columbia for Alberta (if only Charles had abandoned Alberta instead, I may have grown up never knowing that -30 is a thing). Wilfred Laurier was Prime Minister. The Royal Canadian Navy had just been formed. Cars had recently become accessible to the common public. Charles, 10 years Barbara's senior and having been married and widowed, brought five children into his new marriage, the eldest of whom was only 9 years younger than Barbara herself. I often wonder about their family dynamic - did the older kids resent having a step-mother so close in age to them, or did they enjoy having a step-mother they could perhaps relate to? In any case, their family began to grow in 1912 when, at 35, she had her first child, Margaret. Over the next five years, two more children were born - Mavis in 1914, and my grandfather, Frederick, in 1917 - and the family settled permanently on the same block as two of Charles' sisters and their families. Barbara was deeply involved with the Pentecostal Church in Lethbridge, particularly after Charles' passing in 1929. She often served as the Sunday school teacher, and was given the nickname "Grandma" by church members. She apparently had a tough side as well, as her name appears several times in the Lethbridge Herald in regards to the school board wanting to buy her property and her countering with "excessive" offers (which they eventually accepted). When WWII - the fourth of six major wars she would see in her lifetime - began, Barbara became involved in community efforts to send care packages to England, earning yet another mention in the Herald when an Essex resident who once lived in Lethbridge sent a note of thanks to Barbara and another woman. When Barbara turned 100 in 1976, the first mobile phones were being released, Pierre Trudeau was Prime Minister, and the Mach 2 Concorde had just entered service. She had outlived all of her siblings, four of her five step-children, her son, and her grandson. She lived through 6 English monarchs, 15 Canadian Prime Ministers, 6 major wars, and the Great Depression. She saw the first patented telephone and the first mobile phone, the first mass-market automobile and the first jet planes, the first commercial typewriters and the first computers. Her life covered a major period of development and advancement, and on a more personal level, both great tragedy and joy. Barbara passed away on 7 January, 1977, and is buried near Charles in Lethbridge, Alberta. Hands up if you have no idea what "1st cousin, once removed" means. Hands up again if you call the children of your first cousins your second cousins.

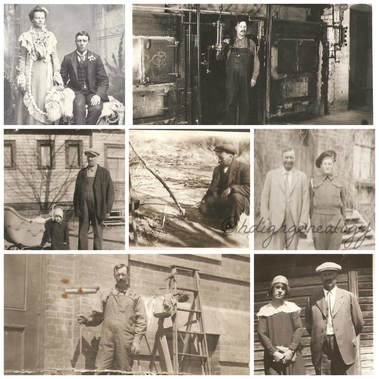

One of the hardest things about beginning one's genealogical journey is having to learn an entirely new language. There are relatives once, twice, three times removed. There are census abbreviations that make no sense whatsoever. There are occupation titles no one in the last century has encountered. There are centimorgans and haplogroups. There are words like "generation" and "cousin" that are used differently in genealogy than in common conversation. Discovering your ancestral history means also discovering a brand new collection of words, terms, titles, and definitions. And few are as frustrating to figure out than the broad assortment of cousins. In order to figure out these familial designations, it's important to understand two things first: one, "cousin" does not just refer to the children of your parents' siblings, as we most often use it. A cousin is anyone with whom you share a common ancestor who is not your sibling, parent, child, aunt/uncle, or niece/nephew. Two, "generation" in genealogical terms does not refer to people born in the same time-frame (we're not talking Gen X or Millennials, here), it refers to how one fits into their family tree. Despite the fact that there is a 30 year difference between my youngest and oldest first cousin, we are all part of the same generation, as we all descend from the same generation - our parents and their siblings. With that understood, figuring out what type of cousin someone is to you becomes considerably easier. We already know that "cousin" refers to someone with whom you share a common ancestor. What type of cousin they are is decided by how you each relate to that common ancestor. First cousins share a common grandparent. You are the generation born to your parents and their siblings. First cousins once removed, then, are people who share an ancestor, but are separated by a generation - your grandparent is their great-grandparent, or vice versa. This can apply to your parents' first cousins, or the children of your first cousins. But wait! Most of us grew up calling the children of our first cousins our second cousins. That's clearly not accurate, so...who are our second cousins? Second cousins, like first cousins, are part of the same generation, only instead of sharing a grandparent, we share a great-grandparent. Or, put another way, our parents aren't siblings, our grandparents are. Still confused? Let's break it down a little more. Siblings=shared parent First cousins=shared grandparent Second cousins=shared great-grandparent Third cousins=shared great-great-grandparent First cousin, once removed=my grandparent is their great-grandparent, or vice versa First cousin, twice removed=my grandparent is their great-great-grandparent, or vice versa Second cousin, once removed=my great-grandparent is their great-great-grandparent or vice versa Second cousin, twice removed=my great-grandparent is their great-great-great-grandparent, or vice versa It all seems very confusing, I know, and no matter how many people explain it in their own well-meaning way, it's likely going to take you figuring out your own system to best remember these various designations. Focusing on the genealogical meanings of "cousin" and "generation" is simply what worked best for me. Good luck, and happy hunting!  I almost titled this piece "Bathsheba Layton, original badass", but that didn't seem appropriate for a number of reasons. It is true, though, that upon discovering my 5x great-grandmother, I immediately felt a sense of pride, respect, and exhilaration. Bathsheba was born on 26 July,1812 in Bedfordshire, England, the eldest of four children born to Samuel Layton and Isabella Wheeler. Her family was not a wealthy one - they were, in fact, quite poor by all accounts. Her father was a struggling farmer, and all four children began working at an early age; Bathsheba took up lace making, a career that would carry her through her entire life. Where her story really gets interesting is around 1831, when she found herself pregnant and unmarried. The father of her unborn child, William Martin, apparently got cold feet - it is said that they were engaged when she told him of her with-child status and that he calmly and cooly responded by...running away. This wouldn't prove effective in the long-term, as two of Bathsheba's siblings married two of William's siblings, undoubtedly leading to some very awkward family dinners, but he did succeed in avoiding any parental responsibility it seems. On the 6th of April, 1832, she gave birth to a healthy baby boy and named him Charles. Charles Layton. Not only did Bathsheba buck the tradition of the time and refuse to give her child up for adoption, she chose to raise Charles alone and give him her surname. Continuing her work as a lace maker, Bathsheba raised Charles as a single mother for four years. In October of 1836, she married Nathaniel Denton, a man 6 years her junior, and the two went on to have seven children of their own. As a teen, Charles converted to Mormonism, and joined his uncle, Bathsheba's brother Christopher, in Utah; so close were Christopher and Charles, many historical records name them as father and son, rather than uncle and nephew. They were also apparently quite persuasive - eventually, most of the Laytons converted to Mormonism and migrated to the U.S. to help establish settlements. Not Bathsheba. As her siblings, nieces and nephews, and even her parents, converted and one by one made their way to America, Bathsheba, Nathaniel, and their children held fast in England. Whatever her hesitation, she instilled it in her children as well. In an 1864 letter to Charles, written the year after Bathsheba passed away, Nathaniel addresses Charles' plea that his siblings convert and join him in America with a kind but blunt "they never shall". While the details of Bathsheba's life and personality are still scant, what we do know about her leaves me in awe: a woman of the mid 1800s making her own living, raising her born-out-of-wedlock son alone and giving him her surname, marrying a much younger man, and firmly rejecting the religious pressures of three full generations is impressive and fascinating, to say the least. I hope that more time and research will tell me more about this remarkable woman. Original badass, indeed. Unless you are First Nations, you are Canadian because somewhere along the way, one or more of your ancestors made the long journey from their homeland to here. This Canada Day, I thought I'd introduce you to the ancestors that brought us here. Charles Henry Harding Born in 1866 in Woodchester, England, Charles was the eldest child of Joseph Harding and Harriett Mills. In 1883, he married Clara Herbert, and the two had three children in England before deciding to move to Canada in 1888. They first settled in Saskatchewan, where he farmed, then moved once more to Lethbridge, Alberta. Clara passed away in 1910, and Charles married my great grandmother Barbara Strachan, also an English immigrant. Charles was an alderman and public servant, working as a census taker and in the accounting department for the city of Lethbridge for a number of years. While it's not entirely clear why he made the decision to move to Canada, it seems it was something discussed amongst his family, as at least two of his siblings also moved here. Charles passed away in 1929. Barbara Edina Strachan Why Barbara chose to make the journey alone from England to Canada remains a mystery, but in 1910, she did just that. First moving to Vancouver and then quickly making her way to Lethbridge, Barbara met and married Charles Harding the following year. The two had three children, my grandfather being the youngest of the three. Barbara was very active in the church and the community, perhaps a result of her outliving her husband by nearly 50 years. She passed away in 1977, 3 months after her 100th birthday. George Foster Stalker & Sarah Ellen EasthopeMy 2x great-grandparents (whom I still do not have photos of! If you do, I would be elated to see them!) were George Stalker, born in 1869 in Franklin, Idaho, the son of Scottish immigrant Alexander Stalker and American Ellen Foster, and Utah native Sarah Easthope, born in 1871 to English immigrants. The two moved to Alberta in the very early 1900s with their two young children, as well as Sarah's two children from a previous marriage. They settled in the Mountain View area, where Sarah's parents already lived, and had five more children there. George was a rancher and trapper, and was active in the LDS church, travelling to England at least once as a missionary. He passed away in 1940, Sarah having died the year before. John Easthope & Sarah Taylor John Easthope was born in Lancashire, England in 1835. in 1856, he married Sarah Taylor, and the two had four children in England. With a group of other newly converted Mormons, the family boarded the Emerald Isle in 1868 for a three month journey to the United States. Sadly (but not unusually), all four children died on the way. They settled in Utah, and had five more children there. In 1873, John took a plural wife, Sarah Naylor (a name that likely caused pre-internet genealogists a lot of trouble - particularly because two different daughters with the same first name were born less than a year apart!) and they had nine children together. John's polygamy caused him plenty of social trouble, and in 1898, he and his first wife moved to Alberta, while his second wife stayed in Utah. John worked for the Union Pacific Railroad while in the U.S., and as a farmer in Canada. He passed away in Cardston, Alberta in 1908.  Sarah Taylor was born in Lancashire, England in 1836. She worked as a weaver both before and after her marriage to John, and was also said to be an excellent singer who often sung at the Temple. She passed away in 1925 in Cardston. Samuel John Layton Samuel was born in 1855 in Kaysville, Utah, son of prominent Mormon Charles Layton and Elizabeth Bowler. In 1874, he married Mary Naylor (if you're wondering if Mary Naylor and the above mentioned Sarah Naylor were related, so did I. Thus far, I've not found a connection, but they did all come from the same general region of England), and the two had one daughter. It's unclear whether Samuel was a polygamist, or if he and Mary split up quickly, but by 1878 he had married and started a family with Sarah Trappett. The two stayed in Utah, having eight children there, before moving to Alberta, where they would have six more children. Samuel held numerous positions in Alberta, owning a general store, working as the local sexton and undertaker, and serving as justice of the peace. He was highly regarded in his community - one newspaper article highlights how what was supposed to be a small family gathering for his birthday turned into a town-wide celebration, and his funeral in 1944 was also a major event. Oddly, his obituary names his wife as Elnora, not Sarah, which suggests he married for a third time after Sarah's death. Sarah Trappett Sarah was born in Norfolk, England in 1859. It is unknown when or why Sarah, her mother, and at least two of her siblings moved to the United States, but we can guess that it had something to do with her father dying in 1870 and Mormon missionaries convincing many English families to convert and move to North America. During her time in Utah, she met and married Samuel Layton, and the rest is detailed above. Sarah passed away in 1926 in Taber, Alberta. William West William was born in Kentucky, USA, in 1828, the eldest son of Hardin West and only son of Catherine Milholland, who seems to have died during childbirth. He apparently married young to an unknown woman, but in 1853, left her and a child behind when she refused to join him in his travels. He spent time in Missouri, Oregon, Wyoming, California - where he hunted gold and was said to have both made and lost fortunes several times over - Idaho, and finally, Utah. Interestingly, during his travels, he expressed his intention to become a Methodist minister and "fight Mormonism", but was later converted and became an active and prominent member of the Mormon church. In 1868, he married Ann Arnell, and the two had five children. In 1883, at the age of 55, he married (or maybe didn't) the much, much younger Mary Taylor, and their daughter Minnie West was born in 1884. Whatever the relationship between Mary and William, it did not last long, and by 1898, he had moved his family, including Minnie but not including Mary, to Alberta. There, he was a carpenter and farmer, helping to develop the Mountain View area and serving the church. He passed away in 1909. Mary Elizabeth Catherine Taylor Since my last post was a lengthy account of what we do, and do not, know about Mary's life, I will just direct you there for the details and give you the short version here. Mary was born in England, and was sent at a fairly young age to live with her uncle, James Kearl, in Utah. It was through James that she met the aforementioned William West, and bore him a daughter. Shortly thereafter, she moved to Colorado, where she met her future husband, Henry Gibboney. The two married in 1892, and had five children in Colorado, before moving to Alberta in 1911. There, Mary reunited with Minnie, and lived twenty comparatively happy years there before passing away in 1931. Of course, this only tells part of the story. All of the above ancestors are from my maternal line; you'll not find any of my dad's ancestors in the story of how I came to be a Canadian, because my dad himself was born in the United States. Born in Lawton, Oklahoma, he met my mother, born in Lethbridge, Alberta, through related churches. They married in 1978, and lived in Oklahoma before deciding to settle in Lethbridge. This just goes to show how fickle our ancestral stories can be; despite the many ancestors that made their way from Europe and the U.S. to Canada, my own nationality could have been entirely different had my parents made a slightly different decision.

I'm glad they didn't. I am thankful that I was born in Canada, and while I have no idea what my life may have been like had I grown up in Oklahoma, I certainly can't complain about having grown up in Alberta and British Columbia. I look back on the many people that led to my being born in Lethbridge and feel a sense of awe that if even one of them had gone a different way, it would be an entirely different person writing this piece. Happy Canada Day to all of those who brought me here.  Mary was a woman of many names and stories, almost all of them difficult to trace or confirm. She has variously been recorded as Mary Taylor, Catherine Taylor, Mary West, Kittie West, Kittie Gibboney, and Mary Gibboney. One family tree I stumbled upon even had her listed as Kittie Kearl - a likely result of her turning up on a census record with her grandmother, Elizabeth Kearl. Even more confusing is her year of birth. While pretty well all sources agree she was born on the 22nd of July, the year has been listed as anywhere between 1863 and 1871 - a huge discrepancy even considering the shoddy record keeping of the time. Mary herself seemed to favour 1871 as her year of birth, but as we will see, she either was not actually sure of her age, lied about it at some point, or let those with inaccurate information do the talking.

Also highly inconsistent is her place of birth. While all of my research points to her being born in England (her parents lived there, her brother was born there, and we know she moved from there), she often gave her place of birth as Scotland: her LDS record, boarding pass, and a couple of census records state this, while two other census records say England, and a death certificate for one of her children says the United States. Why she thought she was Scottish is a mystery - her father was born in Ireland and her mother in England. All of this confusion leads us to...even more confusion. The first time I wrote about Mary, I stated that I had no idea how she ended up in the United States, particularly considering how young she must have been when she moved, seemingly alone (the 1900 census claims she'd been in the US since 1879). Another of her descendants was kind enough to fill me in a little on that - she had apparently been sent to live with her uncle James Kearl in Utah. This makes me wonder if she had been orphaned - we know her father died in 1872, but I have yet to find a record of her mother's death - and sent to the US where she could be with relatives younger than her aging grandmother. It is apparently through her uncle James that she met fellow Mormon William West, a man four decades her senior. Whether their...ahem...relationship was ever made official or not is unclear, but in 1884 (making her, at youngest, 13, and at oldest, 17), she bore William a daughter, Minnie West. Shortly after, William took his family to Canada, leaving Mary behind. At this point, she somehow made her way to Colorado, where she helped run a boarding house, developed tuberculosis, became addicted to morphine, and met her future husband, Henry Gibboney. Interestingly, her brother James was there with her, though I've found no records of him outside England, and have no idea whether he came to the US with her or showed up later. Henry apparently helped Mary overcome her health issues, and the two were married in 1892. Mary and Henry went on to have five children of their own, all born in the United States, and in 1911, the family removed to Canada, partly in the hopes of finding Minnie. The two did indeed reunite, and even had a portrait taken together, marking the first photo of them since Minnie was a baby. Mary passed away in 1931, and is buried in Lethbridge*, Alberta, where much of our family remains to this day. I think about Mary often; not only because her story is a genealogists nightmare, but because it is fascinating, tragic, and makes me wonder so much about who she was as a person. I can't help but wonder how her life - a life that saw her separated from her parents, sent halfway across the world, wed to a man 40+ years her senior, becoming a mother, having her child taken from her and being abandoned, running a boarding house, developing a serious illness and in turn a drug addiction, and getting married once again, all before her 30th birthday - shaped her as a person. A life that almost certainly would have left her wondering where she fit in and who she could trust. A life in which "stability" was likely not part of her vocabulary. I think about how her early life may have informed her later life. Was she a doting mother, or a distant one? Did her inevitable feelings of abandonment make her strong and independent or meek and fearful? I look at the above portrait of her and like to imagine a woman who has seen it all, and survived. A woman who wore the weight of the world on her shoulders, and topped it off with a fancy hat. But the truth is, of course, I have no idea who she really was. It's taken me nearly a decade just to sort out some of the most very basic facts about her, and just when I think I've done that, I am introduced to a new fact that alters everything. Mary may always remain a bit mysterious, but it is that very mystery that keeps me on this journey. *Corrections: -Mary is buried in Taber, not Lethbridge  Note the repetition of names and addresses/areas. Note the repetition of names and addresses/areas. If you were to round up 100 genealogists, whether professional or amateur, and ask them one thing they wish they had known from day one, all one hundred would say "to source everything". Everyone begins researching their ancestry for a different reason - for some it's seeing a photograph of our great-great-grandmother, for others it's being forced to for some junior highschool project. Most of us go into it having no idea that it's going to become a lifelong passion; it is for that reason that so few of us source things properly at first, and it is for that reason that we've all had to go back over our entire tree asking ourselves "where the #*@% did I get that information?" While that is admittedly a valuable learning experience, it's one you should nevertheless be spared. The dead, it turns out, leave paper trails. Census records, marriage licenses, birth and death certificates, wills, newspaper mentions, and baptism records - just to name a few - are out there for most of our ancestors, it's just a matter of finding them. Finding them, however, can be a bit intimidating, as you will be convinced by your Google searches that you have to pay for this subscription or that record, and if you do not have the money to spare, it may seem that there's no hope of collecting these documents. Not true. Sites like Family Search and Find A Grave offer records, portraits, and burial information for free. You can download these images and use them as you see fit. Even Ancestry, which is largely a pay-to-use site, allows you to link records to your ancestors and relatives for free, if you have a tree with them. The catch is that you cannot download them unless you pay for a subscription (pro tip: if you cannot afford the yearly subscription, consider paying for a single month and saving as many records as you can over that time). So, you've got a few tabs open, and you're ready to search for sources. Now what? One would hope it would be as simple as typing in your ancestor's name, and having all their records pop up. Ah, to hope. In truth, you have a lot to contend with. There were probably several people with your ancestor's name living in the same country at the same time. You may not know their date of birth or death, making it harder to narrow down which one is them. Census takers recorded names as they heard them, allowing for many mistakes. Searching for, and sourcing, our ancestors is not purely a matter of pulling up documents, it is just as much an exercise in deduction, in making intelligent guesses, in putting two and two together over and over again. For example, my 3x great-grandfather's name was Benjamin Ellis Trowbridge, and he was born around 1823. I have records, however, that list him as B.E. Trobridge born in 1828, Ben Trawbridge born in 1819, and Benjamin Troridge born in 1821. On the face of it, I cannot be sure that these are all the same person, but I do know that they were all married to a woman named Martha, they all lived in the same city, they all had the same occupation, and they all had a son named Sylvester. There's no such thing as an absolute guarantee in genealogy, but that's about as close as it gets. In seeking sources for our ancestors, we must keep plenty in mind. Things then were not as they are today; I can tell you the exact minute my doctor recorded my birth (7:23 am, if you're curious) - my great-great-grandmother wasn't entirely positive of the year she was born (she favoured 1870, but she turns up on a census record from the late '60s). Not all that long ago, people were far less sure of what year they were born, what country their parents were born in, or their mother's maiden name. Oddly, we ancestral researchers end up knowing more details about their family than they ever did. We have the luxury of the library, the internet, and knowing that we should perhaps cast a wider net. We are able to look through numerous records and compile those most likely to match up to our relative. And that is exactly what we should be doing. We also must be willing to reject sources - the very first John Smith you find on Ancestry.com is unlikely to be your John Smith. This is the biggest issue I see with people's family trees; they are so eager to grow their tree, they do not take the time to really read the documents they are attaching to their ancestors. They add anything they find that has the right name and the right general location, quickly accumulating dozens of "sources", turning their tree into a buffet of information. This, in turn, encourages new researchers to copy some of those "sources", which in turn makes things so much harder for those who want a truly accurate tree. Properly sourcing things takes time. You must be willing to read each document carefully, to do a little math, to seek out clues. And, you must be willing to set aside or outright reject documents that may bear your ancestor's name but no other resemblance. TL;DR: The Quick and Dirty Version of the Above 1. Make it a priority to source everything: names, dates of birth and death, spouse, children, everything. Where you can find those things: census records, birth and death certificates, gravestones/cemetery records, baptism and christening records, obituaries, land deeds, local newspapers, just to name a few. Where you can find those things: Ancestry, MyHeritage, FamilySearch, FindAGrave, Newspapers.com, or, if you happen to live in the same region your ancestors did, your local archives. 2. Cast a wide net. Know that spelling and numbers may change slightly from document to document. If you cannot find any records for your ancestor using the information you've been given, go broader. If you think they were born in 1828, consider looking at 1827 and 1829 births as well. If their last name was Smith, consider that it may have been recorded as Smyth or Smythe. 3. ...but not so wide that it collects everything. Don't add sources just for the sake of adding them - be as certain as you can that the person named in the document really is your ancestor. Read each document carefully, looking for hints that it belongs to your ancestor: does their spouse's name seem right, and does it stay the same/similar from source to source? Is an address listed on the document? Do those addresses match up? If you find consistent facts from document to document, you can feel pretty confident they all belong to the same person. If you don't, you must be willing to discard them, or at least set them aside for further examination. 4. Be patient. Accurately sourcing each and every person in your tree will take time, and while that's not what anyone wants to hear when they're first starting out, I promise you it is a positive. The more time you take in researching your ancestors, the more you will learn about them, and the more you learn about them, the more you'll want to know. And that, that is what this is all about.  My last post was about Minnie West, my great-great-grandmother, a woman I've long found myself fascinated by. I had no intention of following that up with a piece about her husband, my great-great-grandfather Clarence Layton, as I like to change things up and feature a different part of my family in each post. But it just so happened that, while researching my grandmother today, I stumbled upon an interesting little booklet entitled "Golden Memories of Taber Central School". Yeah, I know, that doesn't sound interesting, but it just so happened to have been written by Clarence's step-daughter, and serves as not only a history of the school, but a partial biography, detailing several decades of his life as the school's caretaker. Clarence was born on the 21st of April, 1882, in Kaysville, Utah to Samuel Layton and Sarah Trappett. When he was small boy, the family moved to southern Alberta, where Samuel became a prominent member of the community, holding several positions over the course of his life: justice of the peace, undertaker, grocer, blacksmith, school board member, and Mormon elder. Clarence, too, would become very involved in the community, earning the rank of high priest in the LDS church, and devoting most of his life to Taber Central School. Not a lot is known about Clarence's early life - his father, as mentioned above, held many positions in the community, and Clarence, being his first son, undoubtedly assisted his father in one or more of these jobs. What we do know is that, in 1902, he married Minnie West, and was apparently involved in farming and ranching for the first few years of their marriage. In 1910, with his father as a member of the school board, he became responsible for the gathering and organizing of materials to build Taber Central. From there, he became the school's caretaker, painter, and orderly, and was responsible for maintaining the coal furnace - a job he took so seriously, he actually lived in the school at times to ensure the furnace was always hot. It was this concern, in fact, that earned him his affectionate nickname: Pop Layton. He was perpetually worried about the cold conditions students faced for much of the year, and made a point of bringing the kids that had to walk the farthest or ride in on horseback through the furnace room to get them warm before classes began. Clarence stayed with the school from 1910, when he was just 28, until his death at 72, in 1954. Over the course of those 44 years, he helped build the school, worked as its janitor, caretaker, painter, orderly, furnace man, and cadet advocate. The final entry about him in the book I discovered today reads as follows: In October 1954, a familiar figure at Central, As stated above, Clarence passed away in 1954. His first wife, Minnie West, died in 1929; they were both survived by their eight children: my great-grandmother Dorothy, William, Hazel, Cecil, Viola, Irene, Harold, and Orlin. His second wife, Elva Pickett, died 26 years after Clarence, and they were both survived by their two children, Patricia and Lynn. A hard truth in researching one's genealogy is that you absolutely are going to find that some of your ancestors were bad people doing bad things. When you stumble upon an ancestor who spent their life just trying to be kind, you must embrace them, and Clarence is that person for me. Literally every story about him points to his kindness, his compassion, and his dedication to the good of the community. He fascinates me just as much as his wife, Minnie, does, and I am proud to call them my great-great-grandparents.  Certain ancestors tug at us a bit more than others, for various reasons. Sometimes we feel we can relate to them somehow. Sometimes it's because their stories are fascinating and mysterious, or because we can't find any stories at all. Sometimes we get a sense of loneliness when researching them, and feel compelled to get to know them. When it comes to Minnie West, it's all of the above. Minnie was born in 1884, probably in Idaho, to 56 year old William West, and teenager Mary Taylor. William, already married, took Mary as a second partner, and when the relationship ended almost immediately after Minnie's birth, Mary left the home and Minnie was raised by William and his first wife Ann.  Minnie and Clarence on their wedding day Minnie and Clarence on their wedding day In 1902, less than a year after she shows up as a single daughter in the Canadian census, she married Clarence Layton, son of well-known Samuel Layton and great-great nephew of Mormon pioneer Christopher Layton, in Utah. As Clarence was also living in Canada in 1901, it seems likely that they wed in Utah due to their Mormon roots, especially considering that their first child, my great-grandmother Dorothy, was born in Alberta the next year. Minnie and Clarence would go on to have eight children over the course of eighteen years, all born in the Taber area of Alberta where Clarence worked as a school custodian and jack of all trades. Minnie died at just 44 after "failing to recover from a serious operation". What fascinates me about Minnie is that every "fact" I find about her is uncertain. Her life, much like her mother's, is a bit shrouded in mystery. Her details offer more questions than answers. Why did William take a teenage bride so late in life? Plural marriage was common among Mormons then, but William had been a one-wife man for over 15 years when he married the very young Mary, and had only one child with her before their relationship ended, making it an unusual situation, even for polygamist Mormons. Did she know Mary was her mother, or did she grow up believing Ann was? The few stories that survive about Minnie indicate she had no contact with her mother until the year after her father died, despite them living fairly close to one another. Does this mean she didn't find out about Mary until William died? Does it mean she knew about Mary but was not allowed to see her? Does it mean Mary chose not to contact Minnie, or that Minnie chose not to contact Mary? How did she feel about having half-siblings, through her mother, the same age as her own children? Why, despite her having been well known and liked in her community, is so little about her known today? Every tidbit I learn about Minnie sparks my interest in her anew, and makes me ponder if the image I have formed of her is at all accurate, or marred by all I do not know. I think about her often, and wonder if she could have ever imagined that she, the lone daughter of a rancher old enough to be her grandfather and a teenage immigrant, she, the quiet but busy wife of a school janitor, would so pique the interest of her great-great-granddaughter, born half a century after her death.  It was about this time last year when my hubby asked me what I wanted for Christmas. Approximately 30 seconds later, I was online, ordering an Ancestry DNA kit. When I bought it, I knew next to nothing about genetic genealogy. My hope in testing was that I would put a few family rumours to rest, one way or another, and perhaps chip away at a brick wall or two. I had no idea what to expect, and no idea what I was doing. The test kit took what seemed to me forever to arrive. When it finally did, I busted it open, read the instructions, and cursed a lot. One was not to eat, drink, or smoke prior to taking the test, and I had done all three. I'd have to wait until the next morning. When I did get to take the test, I was overwhelmed by the possibilities. As I spat into that tiny vial, I wondered what I might find. Would family rumours be proved correct, or would they be put to rest? Would I finally figure out who my great-grandfather was? Were there any family secrets lurking out there that my saliva had the power to reveal? I spat. I sealed. I sent. And I waited. And waited. And waited. Finally, I received an email that took me to my results. As I watched Ancestry's fancy-shmancy presentation of the final result, I could barely contain myself; I had heard so many stories from others, ranging from devastating to thrilling, and each one served to feed my anticipation. Would I learn of a new ancestral line? Would I find out my research had led me astray? There were so many possibilities, and I was just seconds away from a whole new world of genealogical discovery. What I actually learned is that I am really, really white. Not at all surprisingly, my results came back as 94% European. The family stories of Native ancestry were immediately put to bed, and those who had heard about an ancestor from somewhere hot and sandy were to be disappointed. What was a bit surprising, however, was the breakdown of my results. All of my research had taught me that the vast majority of my known ancestors were English, Scottish, and Welsh, so the 59% England/Ireland/Scotland/Wales result made complete sense, and was a much appreciated confirmation of 12 years of research. The remaining 35% came as a surprise, though - 21% from "Europe West", which Ancestry defines as "Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein", and 14% from Scandinavia. Aside from a 5x great-grandfather from Germany, I knew of no ancestors from either Western Europe or Scandinavia. A year later, I still don't. While the "ethnicity estimate" was interesting (if grammatically obnoxious), what I'd really been hoping to discover were living relatives. I wanted to see the faces and learn the names of those with whom I shared an ancestor. I hoped to break down a brick wall or two, to find someone out there who knew about the people I did not. I had some cheesy wish that my DNA would be a puzzle piece that would make the whole picture a little clearer. In this, I have been a bit disappointed thus far. While I do currently have 146 "shared ancestor" matches and over 1000 distant cousins, I have learned very little through any of them. Many have no family tree, and few answer messages - they obviously tested for more personal reasons, or lost interest along the way. I've not broken down any brick walls, nor found relatives from lines I didn't already know a lot about. On the bright side, those who do want to communicate are eager and helpful and as thrilled as I am to find a distant relation. They seem to be doing this for the same reasons I am, and I'm grateful for having discovered them. Of course, some fault for not finding more sits with me, as well. Learning about genetic genealogy is almost like learning a new language; there are halpogroups and centimorgans and numbered chromosomes and all sorts of other terms to sort through, and I'd be lying if I said I didn't find it all bit overwhelming. One of my goals for 2018 is to stop procrastinating and actually dig in to what I was so eager to learn, before I actually had to learn it, hopefully leading to a post this time next year in which I share all my new discoveries. Overall, I have found the genetic genealogy experience fascinating, confusing, exciting, and more work than I'd anticipated. I've learned little, but been greatly inspired to continue searching. I now know that many other parts of Europe are holding secrets to my ancestry that I have yet to uncover. I know a little bit more about how I got here, and am driven to learn even more. Oh, and that other 6%? Eurasia, Asia, and Spain. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed